Inside the Lobito Corridor: A firsthand look at Africa’s new trade route

On the margins of the 2025 US-Africa Business Summit in Luanda, Angola, the Corporate Council on Africa (CCA) organized a delegation visit to the Lobito Corridor – an ambitious infrastructure project connecting the Democratic Republic of Congo's (DRC) mineral wealth to global markets

On the margins of the 2025 US-Africa Business Summit in Luanda, Angola, the Corporate Council on Africa (CCA) organized a delegation visit to the Lobito Corridor – an ambitious infrastructure project connecting the Democratic Republic of Congo's (DRC) mineral wealth to global markets

A strategic gambit in global trade

The Lobito Corridor represents more than infrastructure—it’s a strategic play in the global competition for critical mineral supply chains. The U.S.-backed Lobito project offers a strategic pathway for copper and cobalt exports from Africa’s mineral heartland.

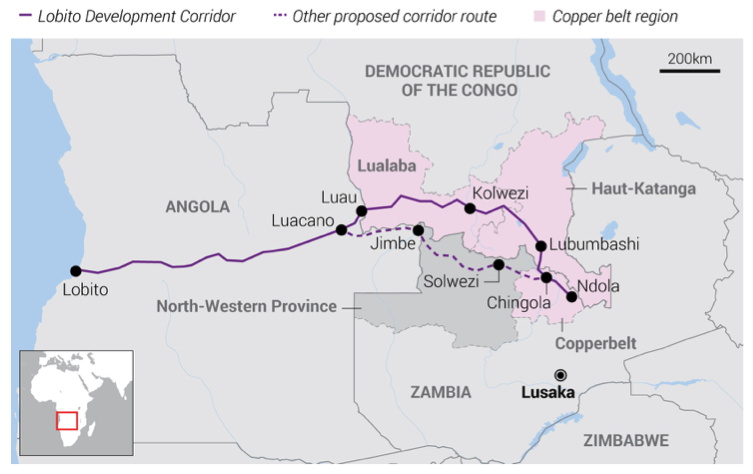

This “mineral heartland” encompasses the DRC’s Copperbelt region around Kolwezi—one of the world’s largest sources of copper and cobalt, essential for electric vehicle batteries—and Zambia’s mining regions. The corridor’s proposed 260-kilometer branch line would eventually connect Luacano (Angola) to Jimbe (Zambia) and onward to Chingola, providing direct access to these critical minerals.

Map of the Lobito Corridor railway connecting Angola’s Lobito port to the DRC and Zambian copper mining regions. (Source: The Lobito Corridor Investment Promotion Authority (“LCIPA”))

Modest but growing operations

At the Lobito Minerals Terminal, operations began 18 months ago with sulfur imports to Kolwezi reaching 10,000 tons per month—approximately 150,000 tons annually. While modest, this represents proof of concept for the 1,700-kilometer route: four days across the 1,300-kilometer Angolan section to Luau, and 4-8 days across the 400-kilometer DRC section to Kolwezi.

The terminal operates under a 30-year concession by Lobito Atlantic Railway (LAR), a joint venture between Trafigura, Mota-Engil, and Vecturis SA. LAR has committed to investing US$455 million in Angola and $100 million in the DRC, including 1,500 additional wagons and 35 locomotives for the Angolan side.

Ivanhoe Mines has signed a non-binding term sheet to transport 120,000 to 240,000 tons of copper products annually starting in 2025—a significant scale-up from current volumes if realized.

Inside Carrinho’s agro-processing complex

The delegation visited Carrinho Industries, Angola’s largest agro-industrial company, whose complex 15 kilometers north of Benguela comprises 17 factories with an annual output of 1.5 million tons. The company’s supply chain illustrates the corridor’s potential beyond minerals.

Carrinho sources inputs from provinces including Huambo (200 kilometers inland from Lobito) and Bié (400 kilometers inland)—both located on the corridor. The company operates:

- Wheat milling: 290 tons per day capacity

- Corn milling: 280 tons per day

- Rice factory: 240 tons per day

- Soybean refinery: 1,200 tons per day, with expansion plans to 4,000 tons per day

- Sugar refinery (under construction): targeting national self-sufficiency and 30% export share

The company’s domestic supply comes from 120,000 hectares of farms: 90,000 hectares of family farming involving 160,000 families, and 30,000 hectares from 60 large-scale farms.

The competition challenge

The corridor faces significant competitive pressures. Most DRC minerals currently ship to China for processing, but the Lobito route—despite being faster overland—faces a longer sea route to China from the Atlantic compared to alternatives through the Indian Ocean.

The Tanzania-Zambia Railway (Tazara), also being upgraded by China, represents one of the many competing routes. Others include the Walvis Bay, Beira, and Durban evacuation routes currently used by miners like Ivanhoe. Success for Lobito may require providing a shorter or cheaper route, but also redirecting mineral exports to the U.S. or Europe, which would necessitate establishing processing capacity, large projects with major viability and execution challenges.

Critical uncertainties

Two key uncertainties emerged from the visit:

- Cargo volume sufficiency: Beyond confirmed Ivanhoe commitments and current sulfur flows, the corridor needs substantial additional volumes to achieve viability. This depends on DRC mineral export patterns, expanded agro-processing in Angola, and potential Angolan mining development.

- DRC rail upgrade timeline: Infrastructure upgrades in the DRC haven’t started yet. A tender is expected in November with a three-year completion target. A timeline that creates uncertainty about full operational capacity within the coming years.

Strategic value of the Corridor beyond economics

Even if Lobito doesn’t become the most efficient route, it offers strategic value for U.S. visibility and influence over DRC mineral exports. This geopolitical dimension may prove as important as pure logistics efficiency in determining the corridor’s long-term success.

The delegation’s visit revealed a project in transition, moving from concept to early operations while facing real challenges of scale, competition, and execution timelines. The Lobito Corridor’s ultimate success will depend not just on infrastructure quality, but on reshaping established trade patterns and supply chain relationships built over decades.

For now, sulfur shipments and modest industrial flows provide proof of concept. Whether interest from mining companies, agro-industrial companies, and other companies will turn into actual cargo volume remains an open question—one whose answer will provide stimulus for economic activity in the region and contribute to impacting the critical minerals supply chain.